“Total Football” turns Portuguese

“Total Football” turns Portuguese

In less than four months, Portugal defend a major tournament crown for the very first time at this summer’s better-late-than-never Euro 2020. Notwithstanding its recent failed UEFA Nations League bid, a lesser-celebrated yet fascinating competition, Portugal’s emergence into unfamiliar territory carries an inherent psychological price tag never before encountered.

External and internal pressure the likes of which only those who have ever worn the grandeur of the name “Champion” will ever know.

For some supporters, such as myself, this is an iconic time. An age in which Portuguese voyagers brave the unknown, becoming club idols in leagues great and small. European heavyweights lacking Portuguese influence become ever rarer, the performance ceiling elevated to still loftier heights. It is the epoch of Portugal’s harvest, that of the Geração D’Ouro’s fecundity, which nearly two decades prior rained down upon and blessed the European continent with a richness even now flowering into the treasure trove of footballing ability to which we are at present beholden.

Where does the road ahead of us lead? To answer that, we must take a detour through the past.

The intellectual giants of football, tactical philosophers from Cruyff to Sacchi to Guardiola, understood the game's inherent paradoxes: seemingly irrational truths or outcomes we find in places which we did not anticipate, are everywhere in football. They knew how to generate attacking movements using defenders, or to think of attackers as the first line of defence whenever possession was lost, for example. These innovations were contrary to the established wisdom of the day which assigned key roles to definite positions in different section of the pitch. In particular, the old numerical system which uniformly conferred the duties and responsibilities of attack and defence to each role. But this neat and tidy manner of describing roles on the pitch did not survive in its original form.

“Trequartistas” or No.10s, gradually faded, for example, and central midfield playmakers now more closely resemble the old No.8s, or box-to-box midfielders. The quintessential No.7 – midfielders operating on the wing to create width by their exceptional speed and technical skill – also went the way of their age as the role of striker, winger, and midfielder merged considerably during the late-2000s & early 2010s as Barcelona and Spain dominated international and club football, respectively. The archaic No.9 - a lone wolf at the pointy end of the spear - has largely been replaced by the false 9. Portugal employed three such midfield-forward hybrids - Bernardo Silva, João Félix, and Diogo Jota - in the UEFA Nations League match against Sweden which Ronaldo missed through injury, a dominant 3-0 victory for the Seleção.

One of the more significant paradoxes of the last decade concerns the emergence of the modern fullback. As wingers became more versatile and moved centrally, fullbacks steadily began to occupy more of the space ahead of them on the wing. Their physical and technical characteristics expanded beyond the routine defensive skillset to include the raw pace and delicate skill on the ball typical of classic No.7s. But just as important was the need for astute positional awareness to offset the inherent defensive liabilities.

In more recent history, tactics began to shift across Europe to manage this risk even further as many clubs employed another central defender to the backline, and the 3-5-2 burst into life. Pep Guardiola and others then made their own adjustments. Many attacking movements begin with the goalkeeper, and with fullbacks in a more advanced position, the assumption of creative responsibilities in the centre often rests with one or both centrebacks in a throwback to Total Football. The 3-4-3 has thus proliferated. All things considered, a flat back four is nearly out of style. Instead, managers exploit the paradox of generating attacking threat from the defensive line through intelligent use of the modern fullback reinforced by technically sound centrebacks or goalkeepers.

But what does all of this mean for the Seleção?

Since at least 2016, Portugal’s talent pool in defence has been questioned ad infinitum. Indeed, how to replace Pepe and José Fonte may create more anxiety in Portuguese supporter circles than how to replace Cristiano Ronaldo someday. Quietly, several of Portugal’s defenders have been instrumental to the aforementioned transformation of football tactics across Europe. Portugal – through Ricardo Pereira, Nelson Semedo, Raphaël Guerreiro, and João Cancelo - has arguably done more than any other nation to facilitate the transition of fullback to multi-purpose wingback.

The utility of these players for their respective clubs varies widely, but each seeks to exploit the bundle of all-around player ability they have at their disposal. Pereira, in addition to his use in a flat back four and in an advanced role in a 4-3-3 or 4-1-3-2, has nearly made himself synonymous with the term wingback, sometimes even fielded on the left of Leicester City’s 3-5-2. Guerreiro has done the same, but his specialty is in combining the responsibilities of a left sided midfield role in a 4-4-2 with those of a traditional leftback better than anyone else in the game. His former teammate, Achraf Hakimi, now does a similar job at Inter Milan. João Cancelo, meanwhile, has innovated a brand new role in the sport, severing the tether between the fullback position and any semblance of order regarding its function – the autonomous, “floating wingback.”

What I am saying is this: the paradox is while we worry how our defensive line can withstand the attacking might of France or Germany, our back four may be our greatest strength.

Our defensive line is not a frailty, but an emergent force. Santos needs to flip the argument on its head and pour attacking venom down the margins of the pitch with our volatile, multi-talented fullbacks. Rúben Dias is mutating into Portugal’s most tactically involved centreback of this or possibly any era of our history. “But José Fonte and Pepe are old.” Both are still in outstanding form for their respective clubs, particularly the former who is statistically this season’s top-rated centreback in Portugal’s arsenal. While it remains true we lack experienced, reliable depth outside these options, the fears Portugal supporters have are over-cooked.

Just imagine Pepe-Dias-Fonte as a central defensive trio with Guerreiro and Cancelo as wingbacks. Admittedly, the 3-5-2 has additional requirements besides good wingbacks, for example, two hard-running forwards. Jota is in this mold, but Félix and Bernardo Silva are not, and Cristiano Ronaldo no longer plays that way. Inter Milan best exhibited the effective use of forward play in a 3-5-2 during their 3-0 demolition of AC Milan. Lautaro Martinez and Romelu Lukaku terrorized Milan’s central defence with searing pace and strength while Achraf Hakimi and Ivan Perisic created threat from the wingback position. Perisic was an especially interesting selection by manager Antonio Conte given his long-standing presence as a classic No.7, which may remind some of Fábio Coentrão’s similar transition from winger to fullback years ago at Benfica.

The new Total Football seems very relevant to the old Portuguese ambitions albeit in a new way. After the Dutch pioneered the 4-3-3 with its twin wing talents either side of a more traditional No.9, Portugal borrowed the formation and revolutionized it through Paulo Futre, Luís Figo, Nani, and of course, Cristiano Ronaldo. How to dominate wide areas of the pitch with pace and trickery defined generations of Portuguese talent, to a fault even. Many have said Portugal do not have a national style of play like the Brazilians, Italians, or Dutch, but this obsessive desire to engage the opposition in one-vs-one contests down the wing is in the Portuguese football DNA. The preservation of this archetypical Portuguese tactic now lies with our fullbacks just when it seemed Portugal too would follow other nations and pool its most talented attacking players more centrally.

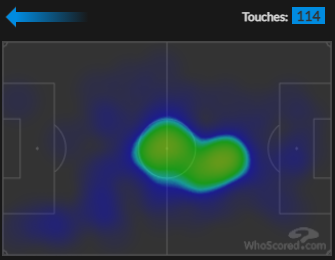

In keeping with the return of Total Football, fullbacks are also now utilized like the deep-lying central midfielders of old. For example, in late February’s Premier League contest between Manchester City and Arsenal, Guardiola fielded João Cancelo at rightback in what was ostensibly a 4-3-3. But Cancelo wandered inside to join Fernandiho in central midfield, occasionally popping up on the right wing or slashing through the right channel. In effect, City operated in a 3-5-2 with Sterling and Mahrez  leading the line in front of a fluid midfield. And who created from deep, you ask? Rúben Dias; with 114 touches and a heat map which would not be out of character for a creative No.6, the traditional deep-lying midfield playmaker (depicted).

leading the line in front of a fluid midfield. And who created from deep, you ask? Rúben Dias; with 114 touches and a heat map which would not be out of character for a creative No.6, the traditional deep-lying midfield playmaker (depicted).

Cancelo also plays left-back whenever Pep wants to include Kyle Walker in the squad. Bottom line, he has been involved in the build-up to more to Man City goals than every other Premier League player except for his teammate, Rodri. İlkay Gündoğan, Kevin De Bruyne, Raheem Sterling, Bruno Fernandes, Marcus Rashford, James Rodríguez, Grealish…none of these is more important to the construction of goal-producing attacks than João Cancelo.

This manner of weapon – hard runner and expert crosser, a fullback-midfielder-attacker hybrid with a good strike from range and the positional intelligence to somehow make it all work – is almost wholly unique in world football today, let alone the Seleção.

The greatest tacticians in football history could not agree on the specific configurations of players, their individual function, or which mode of play was superior – attack or defence. What many seemed to agree upon was the game itself was won or lost on the backline. Paradoxically, the most forward thinking, aggressive managers who prioritized beautiful attacking play almost always agreed that goalscoring moves do not originate on the front line or even in midfield. They are created and sustained by the backline. Cancelo and other Portuguese defenders have proven indispensable to their clubs not for their ability to weather opposition attacks, but by becoming innovative attacking threats themselves.

Whether Fernando Santos is able to weave a championship quality team with these extraordinary threads is another question. But the ingredients are there. Our squad's potential to become an entirely different species to the historical concept of the Seleção in a 4-3-3 grows by the day. Next month's World Cup qualifiers against Azerbaijan, Serbia, and Luxembourg cannot get here soon enough. What is Santos going to do? How exciting!

As for the rest of the squad, considerable disagreement remains about the midfield and attacking players who should accompany Portugal’s greatest ever player for the next two tournaments. Championships which are crucial in the compelling history of a small nation in its struggle to cement itself as a world football power.

Força Seleção.

by Nathan Motz