Maybe it’s the Champions League hype, maybe it’s Monaco’s overachieving efforts reminding me of their last great campaign, maybe it’s me reminiscing of the times in which Portuguese sides got much further in the world’s most renowned club competition than they generally do nowadays…

Maybe it’s the Champions League hype, maybe it’s Monaco’s overachieving efforts reminding me of their last great campaign, maybe it’s me reminiscing of the times in which Portuguese sides got much further in the world’s most renowned club competition than they generally do nowadays…

I’ve been thinking a ton about the iconic Portuguese teams that reached great heights in Europe, and I will now try to apply the style that I use to tactically analyse the teams on PortuGOAL’s Liga NOS series, to some of the most legendary squads that ever came by.

What better way to start than with the last team in Portugal to reach the highest of achievements in European football: the 2004 FC Porto. At a time when there is clear underappreciation for Mourinho despite his outstanding work with Manchester United, this is a reminder of how much he revolutionised the game we all know and love.

---

So, Mourinho arrived at the “Invicta” half way through the 2001/2002 season and would stay for the exact duration of his two-and-a-half-year deal with the club. Mourinho wasn’t 39 yet, and while his work in charge of União de Leiria impressed many, the early enthusiasm was followed by scepticism and a lot of doubt, that grew as the first few months went by.

The team finished third, behind Sporting and Boavista, who were the previous two champions – in January Porto was also behind Leiria, still coached by Mourinho. He’d only be known as the Special One upon his famous first press conference as Chelsea’s new boss, but he sure was special from the start. One of his first press conferences as Porto coach has not been so well documented but was just as punchy in terms of sending out a message. Banging his fist on the table, Mourinho promised Porto would be champions the following season – his first half-season made it three seasons without Porto lifting the title.

He delivered that and more, achieving the treble in 2002/2003 – Uefa Cup, Portuguese Cup (beating his former club in the final) and League title (seven points ahead of Benfica and 17 ahead of third place Sporting), then the league and the Champions League double the following season. Obviously, the Champions League winning campaign is an absolute fairy-tale, and it’s impossible today for a Portuguese side to repeat the feat, achieved thanks to the combination of tactical mastery and innovation, some luck and an underperforming display from what you would call the bigger favourites. Arsenal, Real Madrid and AC Milan all fell in the quarter-finals and Porto ended up facing Lyon, Deportivo and finally Monaco, after that all so iconic night in Manchester.

Many trophies, many victories, let’s look at Mou’s first big job...

Many trophies, many victories, let’s look at Mou’s first big job...

So, during the majority of this time up north, Mou had his side playing in a 4-4-2 with a diamond midfield – even if he still played 4-3-3 during the Uefa Cup winning season. One of the standout characteristics of the way JM approached his Porto project was the way he managed to breathe life into the careers of so many players that were already somewhat past their peak or at their peak. It’s an extremely tough task to absolutely revolutionise a player’s style and form when they are no longer youngsters. It shows how smart, how different and how ahead Mou was communication-wise: a 26 or 27-year-old would only let himself be taught and transformed by a manager if he thought his coach was intelligent enough to earn his trust. Even more so if we are talking about a manager of a young age.

As for transfers, another important factor to take into account is that the manager wasn’t backed by major signings, instead taking advantage of country’s smaller clubs with well-calculated purchases.

Golden partnership at the heart of defence

In a career divided between Porto and Barcelona, Vitor Baía won 33 titles and is one of the best goalkeepers in the history of the sport. Keeping him was a no brainer as long as his injuries kept away from him, but it was ahead of him that a golden partnership was forged: Ricardo Carvalho and Jorge Costa. The latter was the typical, tough tackling centre-back that characterised FCP so well, and who Mourinho did well to rescue. Costa had been sent on loan to Charlton in England due to his rocky relationship with Otávio Machado, Mourinho’s predecessor. Beside him, the suave side of the duo, Carvalho, who was playing his first Porto season after a sequence of loan deals and who would eventually win 89 caps for Portugal, some considering him Portugal’s greatest ever defender. Good on the ball, always perfectly positioned and with an amazing sense of timing, Ricardo was one of the few Mou chose to take to London with him.

Talking Tactics

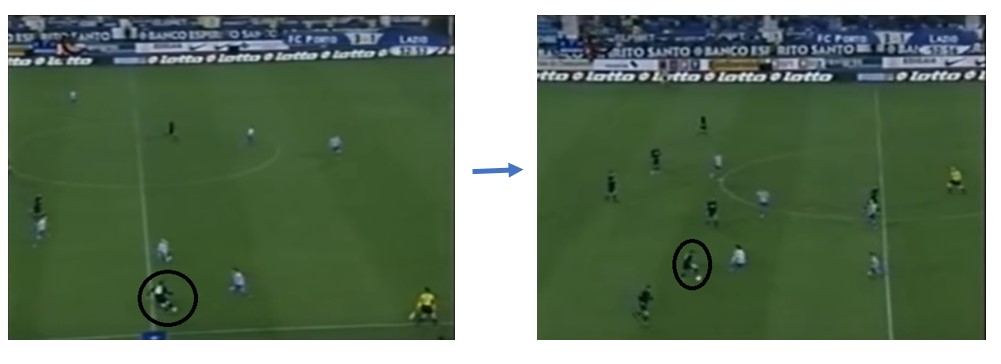

The play of Porto’s fourth goal in what many consider “the match” of the Mourinho era, in which they come back from 1-0 down to beat a fantastic Lazio (Simeone, Chiesa, Stankovic, Mihajlovic) 4-1 at home in the Uefa Cup semi-final.

Vitor Baía hits a long goal-kick to the entrance of the final third. Derlei drops deep and drags his man who he beats to the header, while Postiga sits on the shoulder of his defender. Alenichev moves forward overloading the right side of a broken defence where him and Postiga would combine for the goal.

Porto’s pressure right after losing the ball in the final third not only left Lazio’s men out of solutions and unable to start a counter, it also pushed the man in possession back and allowed the rest of Porto’s players to reorganise.

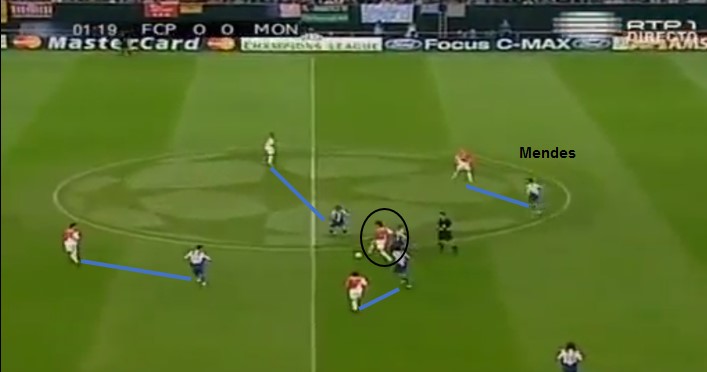

Here we observe Porto’s pressure even better. After a couple of aerial duels, as soon as Monaco get the ball on the floor, Costinha approaches his man while the rest of Porto’s players close all possible passing lanes. Monaco’s midfielder tries to get out of it by passing to the man closer to Pedro Mendes but the Portuguese midfielder recovers it and FCP transition into an attack.

More often than not the team defended in a 4-3-1-2, attacking in a narrow 4-1-3-2. When defending the two deeper lines of players tend to have a short distance between them, but at times the spaces between Costinha and his two midfield partners can create issues defending the half-spaces.

Here we see the best example of a Porto counter with the 2-0 v Monaco in the final. With Monaco pressuring after being down 1-0 halfway through the second half, we see Porto defending very narrow and with a lot of men pressuring the Monaco ball-carrier. As soon as FCP win it back, there’s a 3v3 with Deco leading the line with Derlei and Alenichev. Instead of passing it quickly, Deco overcame a defender first before doing so, therefore making it a deadly 3v2 that would end in his goal. A couple of minutes later a very similar play ended the match.

Complementary full-backs

The team was known for its offensive width, which was given largely by the duo of full-backs. Nuno Valente on the left and Paulo Ferreira on the right. Both were picked up in the manager’s first summer at the club from two smaller Portuguese sides. José knew Valente well after coaching him at Leiria, while Paulo Ferreira had been a consistent performer for Vitoria Setúbal up until then. Valente was the more offensive of the two, which is normal since we’re all aware Mou tends to only allow one full-back to offensively overlap at a time - with the team’s balance always in mind. Ferreira was more complete, solid defensively and didn’t make many headlines while always being crucial for Porto and then Chelsea, where he retired and is now a Director.

Pedro Emanuel - brought from Boavista in the 2nd summer, now Estoril manager - and Ricardo Costa added defensive depth, with the former especially going on to play extensively for Porto long beyond Mourinho’s departure.

Legendary midfield trio

Just ahead an iconic midfield trio rose to the occasion under the young coach. ‘O Ministro’ (The Minister), Costinha, was the balancing point of the side. Arriving at Porto after winning the French League with Monaco, he was mentored by Mourinho who improved his game massively. Positionally very aware, comfortable in possession and off the ball, he never really settled elsewhere after his Porto stint. Further ahead Deco was the main man, who got even closer to a number 10 role in the UCL season, the creative force. His ball-control combined with his capacity to slice divine passes to the forwards was what made the team tick in the attack. Only a few could dribble through tight spaces the way he managed to and added danger to every single set-piece as he stood to take them all. In between them, an odd signing that came good: Maniche wasn’t getting minutes at rivals, Benfica but after making the move north, he completed the trifecta. He added energy in the centre and firepower, both from long range and after penetrating runs due to his box-to-box-ish role.

Pedro Mendes was brought in from Vitoria Guimarães, for the UCL season and was often the chosen fourth midfielder. Taking some of the defensive strain off Costinha. Alenichev, more incisive, was always another option when fit and finally Carlos Alberto came in for the second season as a 19-year-old that could play as the more advanced midfielder or behind the main forward and ended up starting in the final versus Monaco.

Attacking options

The options in the attack were all of Mou’s making. He brought in Derlei, who he coached at Leiria just like Valente, and Jankauskas, the Lithuanian International who had been on loan at rivals Benfica the previous year. While Derlei was a success, Jankauskas was one of the few transfers not to make too much of an impact. He still played a ton, but didn’t have the expected end product and a 20-year-old Postiga took advantage to become a starting option more times than I’m sure he thought he would. Tottenham came in for Postiga in between the two seasons and striker reinforcements were the main necessity to attack the Champions League. In came Benny McCarthy on loan again – the South African forward was on loan at the Dragão in the year of transition from Otavio Machado to Mourinho – to score 25 goals throughout that 2003/04 season.

In this team, forwards needed to be extremely mobile to compensate for the lack mobility elsewhere and to pressurise opposition defences. More so in the first season, Porto became known for their entertaining football, relentlessly (but in organised fashion) pressing opponents in their own half. The forwards’ mobility and work rate was useful for this and to make lateral movements from the centre into wide positions to try and escape their markers.

When it came to their build-up play, they still had a very direct passing style – the long passes would usually come from the full-backs or Carvalho – with frequent narrow long-balls onto forwards who either dropped in between lines and then could combine with the incoming midfielders or ran in behind the opposite defences. Maniche and Alenichev, the sides of the diamond, were charged with being ball-carriers, unlike Deco and mostly Costinha who were more static even in possession.

Shift in style

In the second season Mou got Porto playing a more cautious, narrow style, that didn’t get opened as easily nor did the team press as high as often (despite keeping an intense middle block press). Many considered their style less entertaining but if this approach had not been adopted, it wouldn’t have been possible to reach the latter stages of the Champions League, let alone win it.

As with every Mourinho side, this Porto frequently adapted to the opposition. It was common to see differences between pressure zones, distances between sectors, even slight differences in player roles and movements from match to match, especially in Europe. Let’s not forget Mou was one of the first to analyse opposition in depth and adapt his findings to his game plan.

So there you have it. The greatest two-year spell in the history of FC Porto, and the start of the legend that is the coach José Mourinho. Barring one Portuguese Cup (lost in the final) Mourinho’s Porto won literally everything it was possible to win both domestically and internationally in 2002/03 and 2003/04. A feat that will surely never be equalled.

By Tiago Estêvão