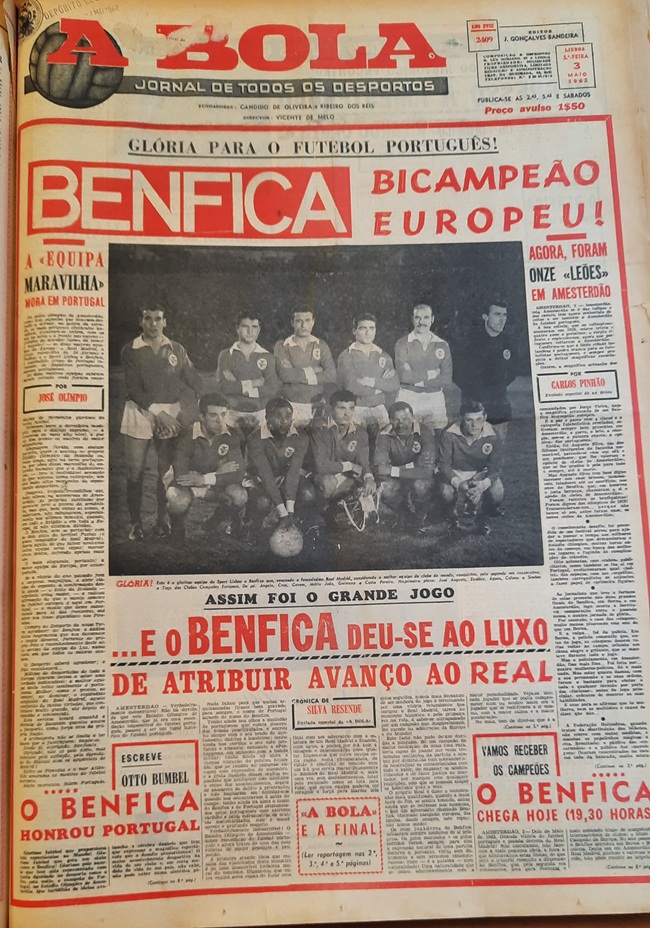

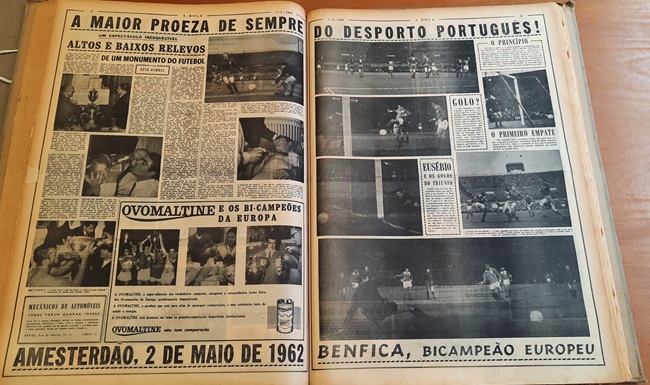

It remains, more than half a century later, one of the greatest football matches ever played. A testament to the greatness of the old sport, and a quick view of what would follow. A match that depended on both individual brilliance and team collectiveness, of vanguard managers and players that defied logic and reason.

The first super-power of continental football against their anointed successors. Football never looked so fresh and fun as when Benfica and Real Madrid met eye to eye in Amsterdam to decide who would be champions of Europe for posterity.

***

Just a year prior, on 31 May 1961, as Benfica supporters celebrated a most unexpected win, beating Barcelona 3-2 in the European Cup final, people in Madrid were laughing and they didn’t hide it.

The almighty Real Madrid had won the first five consecutive European Cup editions, a dominion never repeated as the competition unfolded. They were a team for the ages, the white knights who consecrated and gave relevance to an event that had begun as just a tournament organised by a few newspapers and sports agents. It was Real Madrid who gave meaning to the tournament, and everyone was expecting to see when they would be bettered. It took six years, but in the first round of the 1960/61 season, they met their executioner, none other than the eternal rivals of FC Barcelona.

Madrid had beaten Barça in the semi-finals of the previous edition but were then ousted the following year, with the Catalans taking part once again as they had beaten Madrid to the Spanish title for the second season running. It became all too clear that the cup would remain in Spain as Barcelona booked their way into the final. When they heard it was SL Benfica they were up against, many celebrated beforehand, as Portugal had never even boasted a side that had reached the last eight, let alone take the battle to a continental juggernaut. But they did. Benfica had some help from the crossbar and the Catalan goalkeeper and came out victors 3-2, sparking celebrations all over Portugal and in Madrid as well. After all, Los Blancos dreaded the notion that their rivals would come out winners in a competition that they believed was theirs, and the defeat prevented Barça from adding their first European Cup to an already packed trophy cabinet. They would have to wait 31 years to do that.

Real Madrid fans lap up Benfica’s victory over Barcelona

Of course, Madrid supporters laughed not only because Barcelona lost but because they did so to such an unfancied side. Benfica were known in Spain and Europe at the time, but were far from being considered a continental power. The club had only found itself a proper home seven years prior, with the inauguration of the Estádio da Luz, and despite several trophies collected in the previous three decades that ranked them first in the all-time table of Portuguese football, their city rivals, Sporting, were still considered the more relevant of all the Portuguese clubs.

In 1950, Benfica won the second edition of the Latin Cup – after Sporting had lost the final against Barcelona the previous year – at a time when the competition was gaining relevance in western Europe. It was supposed to bring together the champions of Spain, Italy, France and Portugal at the end of the season. However, the champions rarely attended as they preferred more profitable international tours and the tournament lost relevance over time, and when the European Cup kick-started, the Latin Cup, as well as other regional tournaments, were soon wiped out. In 1956, Benfica lost against AC Milan in the semi-finals of the Latin Cup, while the following year they were beaten by Real Madrid in the final, after ousting Saint-Etienne.

African imports and Guttmann appointment ushers in a new era

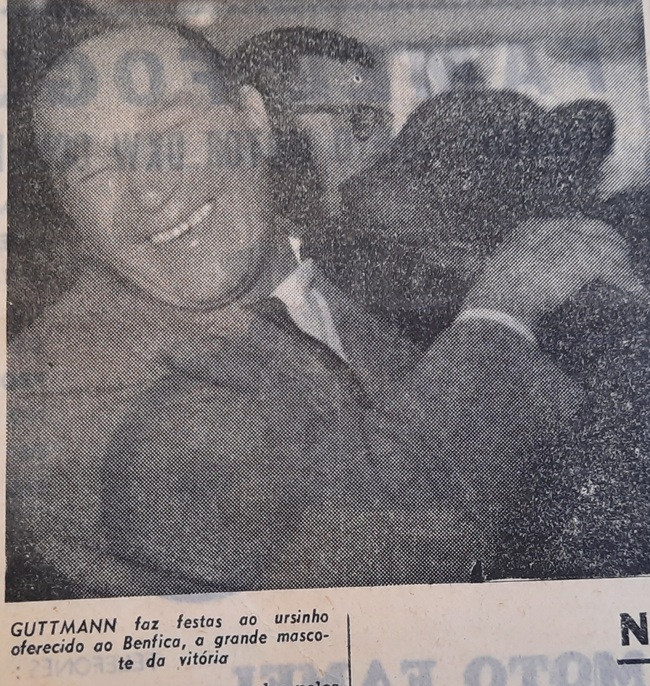

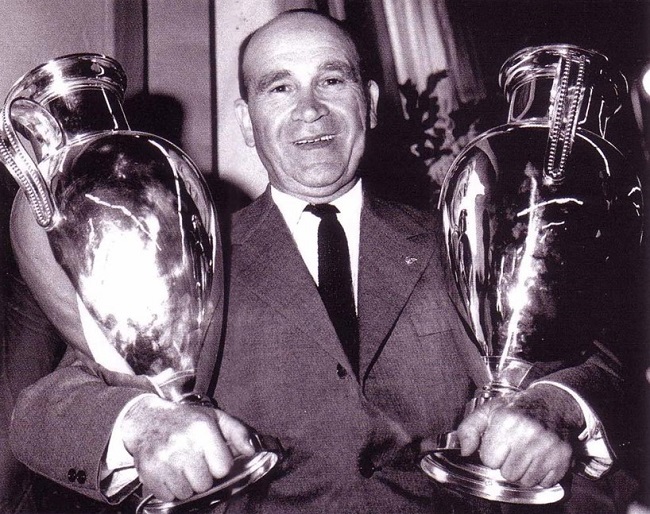

Later in the summer Benfica made their debut in the European Cup. Since the draw was still done by regional slots, they were forced to meet Sevilla and were dumped out immediately from the competition. By then, the club had already started to explore the African market, bringing many promising players from the then Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique. Footballers like José Águas and Mário Coluna became vital to expand Benfica’s attacking prowess, and when they hired Hungarian manager Béla Guttmann in 1959, after he had just led Porto to what would become their last league trophy for almost two decades, the puzzle was complete.

Guttmann installed the Danubian school of tactical principles into the squad and made Benfica one of the most accomplished football sides in the world in just a few months. When they prepared themselves to defend the title won in Bern, few were laughing anymore. Particularly those who had heard all about a young prospect that had just arrived from Mozambique, called Eusébio.

Eusébio’s auspicious debut

The teenage striker was called up to play a friendly against the almighty Santos in Paris but the contract signed by Benfica stated they had to play the first half with the same eleven that beat Barcelona. The Eagles came into the dressing room 5-0 down, and Guttmann sent on Eusébio for the second half. The prodigy scored a hat-trick and impressed Pelé so much that he went over to Coluna to ask about him. Eusébio was a game-changer and arrived at the right time. Benfica’s backbone of the European Cup in 1961 was solid, but with him, striker José Torres and wingers António Simões and José Augusto, Benfica were ready to become the most dominant force in European football for the next decade.

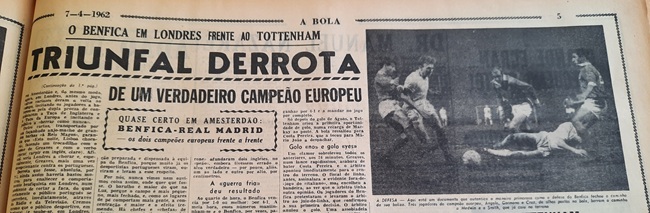

During the European campaign, they thrashed Austria Vienna and Nuremberg before a decisive clash in the semi-finals with favourites Tottenham Hotspur. Guttmann, ever the magician, told the players to warm up on the pitch – something not very common at the time – so that they could feel the hostile atmosphere beforehand and have time to digest it. It worked wonders. The Eagles had won 3-1 at da Luz and lost 2-1 in London, which was enough to get them through to their second consecutive final in the competition.

Real Madrid packed with scintillating but ageing stars

Real Madrid, on the other hand, had barely changed from the side that the world so greatly admired, but their star players were getting older. Alfredo di Stéfano, the world’s best player, was now 35. Ferenc Puskás, the Hungarian striker, was 33 and centre-back José Santamaria was 32. Only Francisco Gento, the speedy winger, was below his thirties, but he was 29 by the time the final came around. Veterans of a thousand battles won, yes, but without the physical ability to run for the entire 90 minutes against a fresher side. Nonetheless Madrid, who knocked out Vasas, Boldklubben 1913, Juventus – after a hard-fought playoff – and Standard Liege, landed in Amsterdam as undisputed favourites. The crowd flocked to the Olympic ground just to see them lift what would have been their sixth trophy in seven editions of the European Cup. Benfica, it seemed, was just happy to be there. Spoiler alert; they weren’t.

Guttmann’s plan

Béla Guttmann had a plan. He knew that Real Madrid lived and breathed for what Alfredo di Stéfano thrived for. Eusébio, now a regular first-team starter, had displaced Mário Coluna, once a formidable forward, to a central midfield position, so the Hungarian had him man-mark the Argentine for the first half. As both sides played in a mix of the WM with a more modern 4-2-4, with players roaming freely so that they could either form a back four line or drop deep from the central striker position, it became a very mobile playground for the more talented and creative players, and nobody could beat Di Stéfano in that scenario.

Playing in all blue – a secondary kit Real Madrid started to use in the 1950s when their popular purple kit, inspired by the Republican flag, was quietly put to rest – the five-time winners quickly showed more than 60,000 supporters who packed the ground, and the millions who watched on television, one of the first sports events broadcast to more than 14 different countries live, what they were all about.

Ferenc Puskás in a rush, Madrid race into two-goal lead

In the 17th minute, a defensive clearance by Madrid ended up at Di Stéfano’s feet, and without letting the ball touch the floor, he sent a through pass into space where Puskás ran onto it before smashing the ball into Costa Pereira’s net. Three touches on the ball followed by a penalty on the move, and Madrid were 1-0 up. It seemed their arrogance had substance to it still.

Just to make a point, five minutes later, the Hungarian scored again. Collecting the ball halfway inside Benfica’s half of the pitch, he blasted a powerful shot that Pereira somehow foolishly allowed to pass by him. A poor attempt at a save by the Portuguese international, but Guttmann was probably more enraged because Puskás had been left all by himself and had all the time in the world to wind up his world-renowned left-footed shot.

Benfica roar back

It seemed it was game over, but things were just getting started. Far from letting themselves be consumed by despair, the Benfica players looked at each other and rampaged towards José Araquistáin’s net. Two minutes later, they pulled a goal back. After a foul on Eusébio on the left side of the attack, Coluna feigned to take the free-kick only to slide the ball back to the young prodigy. Eusébio’s thunderous shot hit the post and, as he so often did, José Águas found himself in the right place at the right time to guide the ball into the empty net.

With Guttmann insisting that Benfica press as high as possible to squeeze Madrid’s creative play, in the 33rd minute, Cruz managed to steal the ball from Luis del Sol before passing it quickly to Cavém, whom he played a quick one-two with before releasing the ball to Águas, who had drifted to the right. The team captain crossed the ball into the box where Eusébio was surrounded by markers, but somehow he managed to control the ball, and before any defender from Madrid could reach it, Cavém appeared out of nowhere to blast a shot that would end up in the net. 2-2, game on.

Real Madrid retake lead but Benfica sense blood

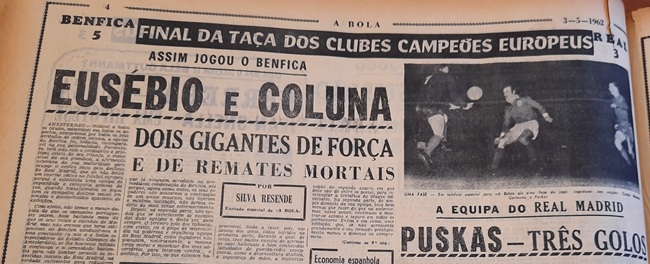

So it seemed. But Puskas wasn’t finished. He scored four goals in the 1960 European Cup final, after he had been forbidden from playing in the previous season’s final in Stuttgart against Stade de Reims because of public allegations claiming the West Germany players had been doped when they beat Hungary in the 1954 World Cup final. And the great Hungarian completed his hat-trick just before the break after a neat combination with right winger Tejada.

Real Madrid led at half-time, but there was a feeling in the air that they were already physically worn out. A young Johan Cruyff, who worked that day as a ball boy, looked on in awe at Di Stéfano, but he too had the same feeling as he admired how Eusébio and the red shirts seemed fitter and lighter while moving around the pitch.

In the dugout, Guttmann expressed his pride at how his players had performed and told them everything had gone according to plan. Now it was time to release Coluna from his man-marking duties and let Di Stéfano try chase him. Benfica had been the better side in the first half, despite the result, and they began the second even better. The ball moved quicker, and so did the Eagles. Six minutes after the break, Coluna proved Guttmann was right by scoring a third for Benfica, via a trademark long-range shot.

Eusébio takes over

With the midfielder now free to dictate the tempo of the match, it was time for another Mozambican to shine. Eusébio had been moving behind Águas, but Guttmann told him to roam more freely in the second half in search of space. He was often dropping either to the left or right to disturb Madrid’s compact defensive line, and, in just three minutes, he settled the match in exactly the same way he would do to any team that crossed paths with Benfica for the following decade.

In the 63rd minute, Eusébio dropped as deep as the right-back position to pick up the ball from Germano and started to sprint on the wing, changing pace as he ran. Di Stéfano, who quickly understood what he was up to, tried to follow him but simply couldn’t. Eusébio was too fast for the veteran forward. When he moved inside to shoot, Pachin appeared to block him, and Eusébio ended up on the floor. Penalty for Benfica. José Águas was the usual taker, but Eusébio then famously approached Coluna and asked him if he could ask “Mister” Águas if he would allow him to take the shot. Coluna smiled, told Águas that the boy seemed inspired enough, and Eusébio coolly made it 4-3 for the Eagles.

“The King is dead, long live the King”

Two minutes later, and after Di Stéfano had his best opportunity of the night, only to be denied by Costa Pereira, Eusébio was at it again. A Santamaria handball right in front of Madrid’s goal resulted in a free kick that Eusébio smashed into the net to make it 5-3. Amsterdam was in awe of this new wonderkid, and world football would never be the same after that night. The King was dead, long live the King. Di Stéfano, who had ruled supreme in continental football for almost a decade, was about to be replaced by a player who had only arrived in Lisbon under the false name of Ruth a year prior.

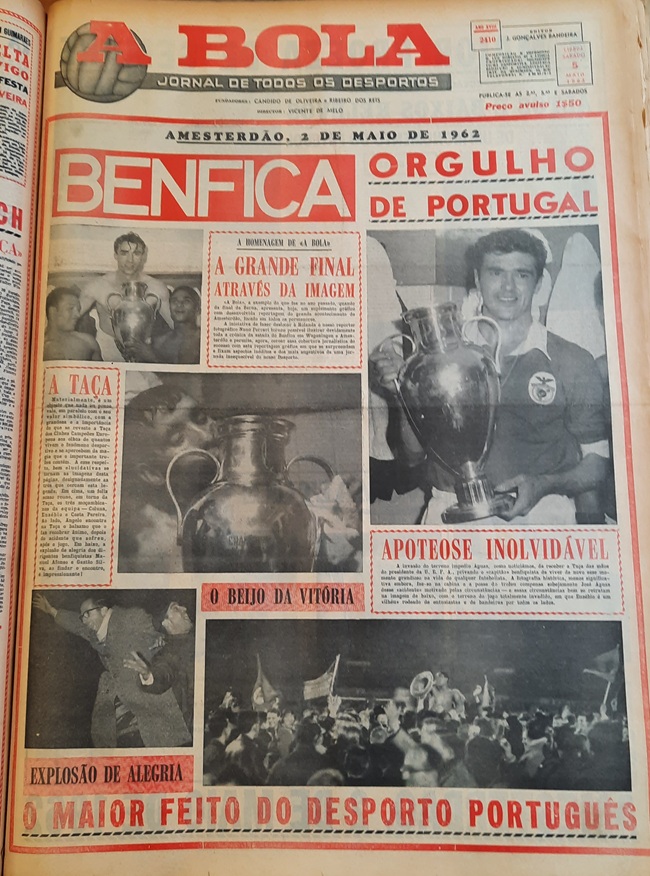

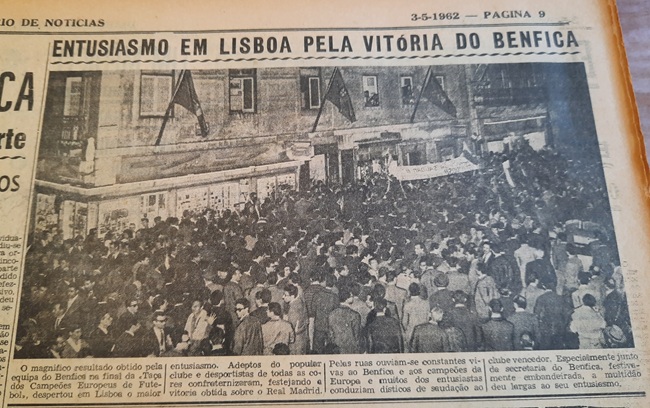

For the following twenty minutes, Real Madrid tried their best, but they had nothing left in the tank as Benfica kept their composure and knew how to keep the ball rolling without giving away too many chances. When the match was over, Eusébio ran towards Di Stéfano to exchange his shirt with his idol. He then tucked it inside his shorts as the crowd picked him up to parade him around the pitch. With one hand on his shorts and the other punching in the air, the pitch invasion that ensued caused chaos but stole not a shred of enjoyment from the players and staff who had just made history.

Benfica became European champions for the second time and, suddenly, with Eusébio, it didn’t seem fanciful that the former underdogs were actually up to the task of equalling Madrid’s five crowns.

Benfica would indeed play in three other finals during the decade and could have won every one of them. Coluna’s injury the following year at Wembley – at a time when there were no substitutions available – Pereira’s poor night in San Siro in 1965 and Eusébio’s last minute failed opportunity against Alex Stepney in 1968, separated Benfica from ending the 1960s ranking practically alongside Real Madrid, who played and lost the 1964 final before coming out winners in 1966, their last trophy until 1998.

Amongst the greatest ever finals

The Amsterdam final ranks as one of the most exciting and high-scoring European Cup or Champions League finals ever played, arguably only rivalled by Madrid’s 7-3 win against Eintracht Frankfurt in 1960 and PSG’s demolition of Inter in 2025. A memorable sporting event that was quickly added to the hall of fame gallery of matches that defined what the game was all about. The best side of the 1950s against what would become the best side of the 1960s, two rival Iberian nations facing each other and the two most decisive players in European football over the span of twenty years.

Real Madrid and Benfica met once again in 1965, with Benfica once again coming out on top, Eusébio in unstoppable form in the first leg during a 5-1 demolition of the Merengues. Curiously, following that tie, the two teams did not face each other again until the last day of the 2025/26 Champions League group phase, when Anatoliy Trubin’s dramatic goal in stoppage time for Benfica set up another duel in the competition, a play-off to reach the round of the sixteen. After 60 years of not playing against each other, the two Iberian titans would meet three times in the space of a month.

Madrid stockpile trophies, Benfica “cursed”

By then, Real Madrid had accumulated 15 wins in the competition while Benfica became known as the side with the most finals lost in the history of the competition, adding two more to those three played in the sixties, in 1988 and 1990, to give credence to the so-called Guttmann curse. The Hungarian manager is said to have stated in a fit of rage that the club would not win another European Cup in 100 years after his request for an increase in wages was refused and he was summarily sacked by the Lisbon outfit.

Whether or not those words were actually proffered is up for conjecture, but the Benfica board decided it had been the players, and not the manager, who made the team tick. Neither Guttmann, nor Benfica (to date) ever won a continental trophy again, leaving room for the imagination regarding what might have been if the Eagles hierarchy had decided to reward the manager for his service and he had remained at the helm of his brilliant young side.

By Miguel Lourenço Pereira, author of “Bring Me That Horizon – A Journey to the Soul of Portuguese Football”.